The Taiwan Firm That Makes the World’s Tech Run

Inside its boxy off-white headquarters in sleepy Hsinchu County, technicians in brightly hued protective suits—white and blue for employees, green for contractors and pink for pregnant women—push polished metal carts under a sallow protective light. Above their heads, “claw machines”—nicknamed after the classic arcade game—haul 9-kg plastic containers containing 25 individual slices, or “wafers,” of silicon on rails among hundreds of manufacturing stations, where they are extracted one by one for processing, much like a jukebox selecting a record. Only after six to eight weeks of painstaking etching and testing can each wafer be carved up into individual chips to be dispatched around the planet.

The $550 billion firm today controls more than half the global market for made-to-order chips and has an even tighter stranglehold on the most advanced processors, with more than 90% of market share by some estimates.

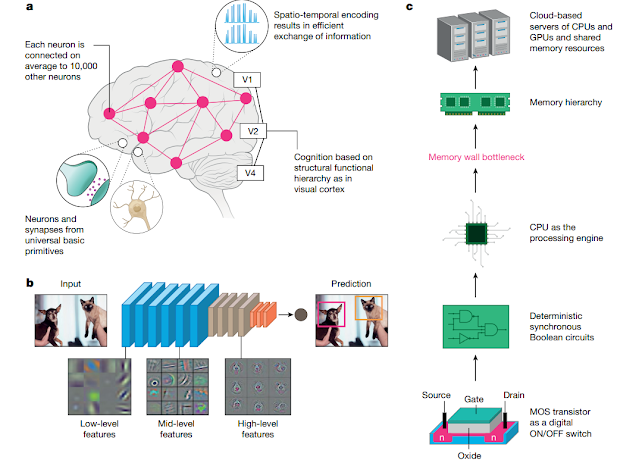

The importance of semiconductor chips has grown exponentially over the past half century. In 1969, the Apollo lunar module sent tens of thousands of transistors with a combined weight of 70 lb. to the moon; today, an Apple MacBook crams 16 billion transistors within its total weight of just 3 lb. The prevalence of chips will keep rising alongside the spread of mobile devices, the Internet of things (IOT), 5G and 6G networks and a growth in demand for computing power. Global chip sales were $440 billion in 2020 and are projected to grow over 5% annually. President Joe Biden calls them “critical products” whose “supply-chain disruptions can put Americans’ lives and livelihoods at risk,” while the governments of Japan and South Korea compare the importance of semiconductors to “rice.”

Making chips is so unbelievably complex and specialized that diversifying the location of fabs will make it more difficult to maintain quality. The transistor in a 3-nm node is just 1/20,000th the width of a human hair. Were you to enlarge a foot-long wafer of semiconductor to the size of the continental U.S., the required patterning for these chips would still be only the width of a thumbnail. The key component may only be silicon—or purified sand—but the magic happens in how it is processed and manipulated. “It’s like baking bread,” says the TSMC section manager. “The ingredients are pretty much the same, but how long should you bake it, what temperature should it be, that’s what matters.”

For this reason, TSMC’s foundry is meticulously controlled. All visitors must don head covers, dust-free jackets, pants and shoes before passing through an “air shower” to remove errant particles. The extreme ultraviolet lithography machines that TSMC uses each cost around $175 million. Larger fabs will have 20 of them. Creating a chip takes around 1,500 steps, each with 100 to 500 variables. Even if each step’s success rate is 99.9%, that means less than a quarter of the final output is usable. “Is there something slightly different in the water or the air or the chemicals in Arizona?” asks Hanbury. “The R&D team is not going to be a bullet train away to solve these problems.”

If you want to learn more about TSMC and semiconductors, have a look at this video here: Secretive Giant TSMC’s $100 Billion Plan To Fix The Chip Shortage - YouTube

Comments

Post a Comment